Ferns of Maine: a Brief Guide

What are ferns? How can you tell them apart? And what do they do?

Ferns are not particularly glamorous. You can find them in almost any forest, growing in sandy barrens, floodplains, and rocky crags. But there is more to this unassuming character than meets the eye. As evidenced by their ubiquitous presence across much of the globe, ferns are survivors, persisting for hundreds of millions of years through dramatic shifts in climate and landscape. Despite their modest reputation, ferns offer a fascinating glimpse into plant evolution and ecological adaptation. The best part? You can find them in your own backyard!

This article seeks to educate residents of Western Maine about these often-overlooked members of the Plant kingdom. To start, we’ll go over the evolution and reproductive strategies of ferns; next, we’ll tackle the “anatomy” of a fern; and finally, we’ll look at some common and rare fern species that are native to Western Maine, and what they do for your forest.

Ferns are some of Earth’s oldest plants. The first ferns appear in the fossil record almost 400 millions years ago. Though mosses and their relatives are generally thought to be the first land-dwelling plants, ferns and their relatives are the oldest vascular plants — the most dominant group of plants on Earth today. Unlike mosses, vascular plants have specialized tissues (xylem and phloem) that transport water, nutrients, and sugars, allowing them to grow larger and inhabit a wider range of environments. With this advantage, ferns quickly spread across the globe during the Paleozoic Era. At one point, vast forests of ferns as tall as modern trees covered much of the landmass of prehistoric Earth; the remnants of these forests make up the majority of our planet’s coal reserves. During the Mesozoic Era, these fern forests were gradually supplanted by forests of gymnosperms (conifers) and angiosperms (flowering plants), although certain species of “tree ferns” remain in the tropics to this day.

The life cycle of a fern is distinctly different from that of other vascular plants, alternating each generation between the sporophyte (diploid) and gametophyte (haploid) stages. If you also barely remember your high school biology class, I’ll give you a quick refresher: haploid cells or organisms have a single set of unpaired chromosomes, while diploid cells or organisms have two sets of chromosomes, one from the egg and one from the sperm. The mature fern plant that we are familiar with is the sporophyte, which produces spores on the underside of its fronds. When released, these spores germinate in moist conditions, growing into a small, heart-shaped gametophyte (prothallium). The gametophyte develops reproductive organs: antheridia, which produce sperm, and archegonia, which contain eggs. Water is required for fertilization, as sperm swim to the egg, forming a zygote — a diploid organism. This zygote grows into a new sporophyte, eventually developing fronds and completing the cycle.

This antiquated reproductive system is a little clunky — gymnosperms and angiosperms have more efficient reproductive strategies — but in spite of their shortcomings, ferns’ ability to thrive in shaded, humid habitats and regenerate after disturbances has ensured their survival for hundreds of millions of years. It is important to note that ferns often produce both fertile and infertile fronds in the sporophyte stage; these can be useful tools for identifying species of ferns that appear similar but have markedly different fertile fronds. Furthermore, some ferns (Bracken fern, for example) are known to reproduce asexually, spreading through rhizomes and creating large, clonal colonies. The disadvantage of this method, of course, is that genetically identical clones are more susceptible to disease and disturbance. But by balancing sexual and asexual reproductive strategies, ferns continue to adapt and thrive in Maine’s forests and fields.

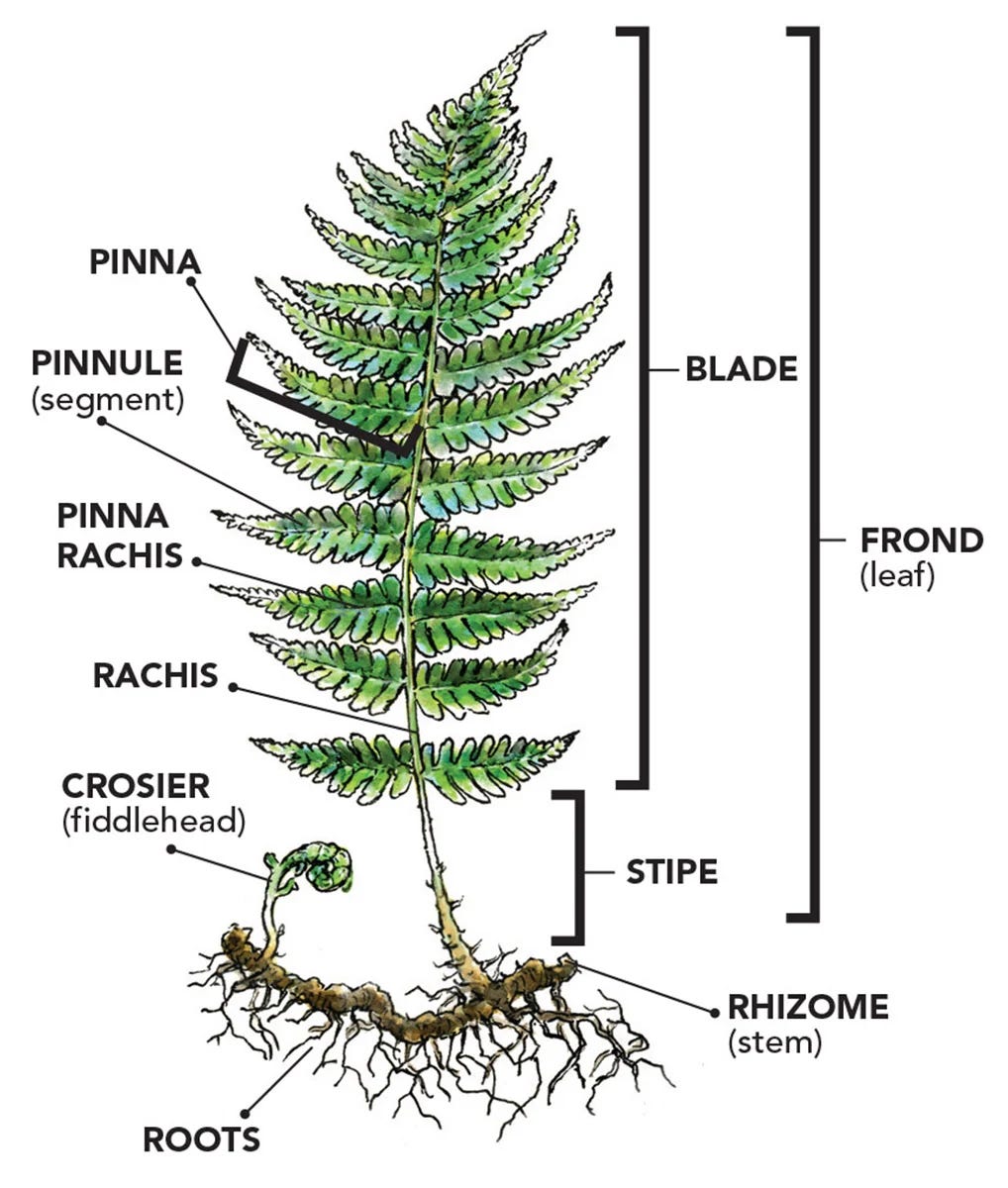

Western Maine is home to dozens of species of ferns; in this article, I’ll introduce some of the most common species, as well as a few of the rarest. However, to the untrained eye, many of these species look nearly identical. To help the reader differentiate between species, I’ve produced a list of helpful definitions that pertain to the “anatomy” of a fern — the diverse structures and parts that make up these surprisingly complex organisms.

Frond: The entire fern leaf, including the blade and stipe.

Blade: The broad, leafy part of the frond.

Stipe: The stem-like structure that supports the blade and connects it to the rhizome.

Rachis: The central axis of the frond that runs through the blade, from which leaflets (pinnae) emerge.

Pinna (plural: Pinnae): The primary leaflets that grow on either side of the rachis.

Pinnule: A smaller division of a pinna, present in highly divided fronds.

Rhizome: The underground or horizontal stem that anchors the fern and produces roots and fronds.

Sorus (plural: Sori): A cluster of spore-producing structures (sporangia) found on the underside of fronds.

Sporangium (plural: Sporangia): A small structure within the sori that produces and releases spores for reproduction.

Armed with these definitions, let’s dive into the amazing diversity of ferns in Maine!

Maidenhair fern

The northern maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum) is one of New England’s most recognizable ferns, with its characteristically delicate fronds and shiny, dark stems. You can find it growing in rich forests, along rocky streams, and in misty ravines. It is associated with northern hardwoods like sugar maple, American beech, and yellow birch.

Hay-Scented fern

Though somewhat difficult to distinguish from wood ferns, the hay-scented fern (Dennstaedtia punctilobula) can be identified by natural context: it often grows invasively and abundantly in disturbed forests, meadows, and fields to a maximum of two feet. Unsurprisingly, when crushed, the fronds give off the scent of fresh hay. It is “thrice-cut,” meaning the pinnae are divided three times: once at the rachis, once at the pinna rachis, and once within the pinnule itself. A large patch of this fern is a tell-tale sign of deer-overbrowse, as deer generally do not consume the hay-scented fern. It is often associated with red maple in the overstory.

Interrupted fern

The interrupted fern (Osmunda claytoniana) is commonly found in clumps along moist ravines and wetland margins. It can be confused for the cinnamon fern; however, the tips of the cinnamon fern’s pinnae are more pointed, and it produces a separate, cinnamon-colored fertile frond. The interrupted fern grows up and out in a vase shape, usually to 2-3 feet tall but occasionally to five feet. The small, fertile middle pinnae create an “interruption;” hence, the fern appears to be vertically divided into two sets of pinnae.

Rock Polypody

Rock polypody (Polypodium virginianum) is a small fern found on thin soils, often on ledges or boulders in hemlock stands. The frond is divided once at the rachis, but the pinnae are not divided. Native Americans used rock polypody to treat colds, coughs, and stomach pains. The name “polypody,” meaning “many little feet,” is derived from ancient Greek and may reference the foot-like appearance of the rhizomes.

Ostrich fern

One of Maine’s largest ferns, the ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) is especially coveted in the spring for its edible fiddleheads. It is one of our tallest ferns, reaching over 5 feet tall; it can be distinguished from other tall ferns like cinnamon fern and interrupted fern by its arching, feathery form and its green-brown fertile frond, which appears later in the summer. Its fiddleheads can be identified by a fragile, papery brown sheath. Ostrich fern can be found along stream-banks and in other moist forest environments.

Sensitive fern

The sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis) is an attractive fern that grows best in wet thickets, swamps, and meadows. It has a remarkably prehistoric appearance; in fact, based on 60 million-year-old fossils, we know that the sensitive fern has changed little since the Paleocene epoch. Its fronds are pinnatifid, meaning the pinnae are divided from each other and almost from the rachis. The sporophylls (fertile fronds) produce clusters of berry-like sporangia that give it the nickname “Bead fern.”

Bracken fern

Bracken Fern (Pteridium aquilinum) is so successful that it is found on every continent except Antarctica. It is quick to bounce back after disturbances, often forming weedy colonies that impede the regeneration of other plants. Its distinctive frond is easy to identify; the tripartite blade is tripartite and often horizontal to the ground, growing up to 4 feet.

Marginal Wood fern

The marginal wood fern (Dryopteris marginalis) is arguably the most common wood fern in New England. It looks very similar to the hay-scented fern, but can be identified by the characteristic pattern of sori located around the edges of its pinnae and its darker shade of green. This fern remains green throughout the winter and prefers moist, slightly acidic forest soils. There are nine different species of wood fern in Maine, ranging from the common intermediate fern to the rare male wood fern.

Green Mountain Maidenhair fern

Adiantum viridimontanum, or Green Mountain maidenhair fern, is a rare fern species that grows exclusively on serpentine rock outcrops in the mountains of Vermont, Maine, and southern Quebec. Its specific taxonomy and genealogy have been subject to debate since its formal description in 1991. It is likely a hybrid between A. pedatum – the northern maidenhair fern – and A. aleuticum, a western fern found rarely in maine. The green mountain maidenhair fern is an example of an allotetraploid organism; this means it has four sets of chromosomes, derived from two different species and formed through hybridization. For information on distinguishing between the three species, see this guide from the Maine Natural Areas Program.

Male Wood fern

The male wood fern (Dyopteris filix-mas) is rare throughout its range in the United States, though it is found more abundantly in Europe. It inhabits rich, rocky forests and is associated in Maine with calcareous ledges and talus slopes. It can be distinguished from the Marginal wood fern—its close relative—by its rich green (rather than blueish) color, short petiole, and clusters of sori located close to the midvein of the pinnule, rather than the margins. Due to its rarity, D. filix-mas is prized by collectors and may be in decline throughout much of its range.

Broad Beech fern

In Maine, there are two types of beech ferns, belonging to the genus Phegopteris: the broad beech fern (P. hexagonoptera) and the long beech fern (P. connectilis). The broad beech fern is considered rare in Maine—it’s at the Northern edge of its range—while the long beech fern is common. The two can be differentiated quite easily: broad beech fern is wider than it is long, while long beech fern is longer than it is wide. P. hexagonoptera also has a “wing,” or a piece of connective tissue, that lines the main rachis between the pinnules; P. connectilis, in spite of its name, does not possess this piece of tissue. In Maine, the broad beech fern grows in the mesic soils of rich hardwood forests—hence the name “beech fern.”

It is easy to dismiss ferns as insignificant members of the plant kingdom. In reality, however, ferns function as ecological indicators, food sources, nutrient cyclers, and soil stabilizers. Pioneer species like Bracken fern reliably reappear after disturbances, providing shelter for recovering biota; ostrich ferns provide fiddleheads for wildlife forage and human consumption. For forest landowners of Maine, recognizing the ecological value of ferns can inform sustainable land management practices, ensuring that these often-overlooked plants continue to support biodiversity and forest health for generations to come.

As always, you can send any questions or comments to oxfordcountycts@gmail.com!